4th Sunday of Easter

The Book of Revelation

The Church is cautious with the Book of Revelation. There are only seven occasions when that book is an official Sunday reading. The first is on the Feast of Christ the King in Year B of the Sunday cycle. The remainder occur on the Sundays after Easter Sunday in Year C.

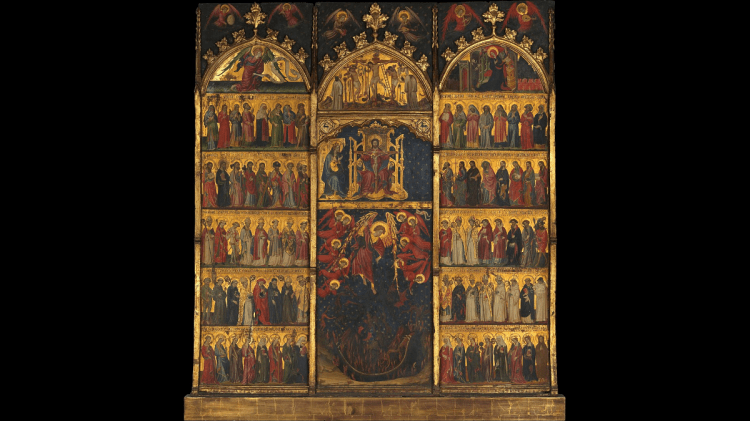

An obvious symbolic features of the Book of Revelation is its frequent use of the number “seven”, signifying completeness. One set of seven in Revelation, after the seven letters of chapters 2-3, is the breaking of the seven seals, which extends over four chapters (4:1-8:1). In the long interval between the sixth and seventh seal, the author returns to the vision of heaven. A change has taken place, between before and now, the difference is the presence of human beings in heaven. Previously these had been counted as numbering 144,000 from the tribes of Israel, but now, there is the realization that they cannot be counted, due to their great number. These are the martyrs, who come from every tribe and nation. Though they suffer no more, their state is described in words from Isaiah: they suffer neither hunger nor thirst (Is 49:10).

Once more Christ makes His appearance, this time not just as the Lamb but as the Shepherd. Note the parallel with Saint John’s Gospel where you find the fullest self-description of Christ as the Good Shepherd (Jn 10:11-18). Verses from chapter seven of Revelation are annually read on the Feast of All Saints. The vast numbers recorded serve as a reminder of the multitudes who have followed Christ, who are not listed in official lists of canonized saints, though many of whom have given their lives in martyrdom. It is the vocation of every Christian to be a saint, which is the word Paul uses when he addresses the Christians of Rome (Rom 1:7).

Up to this weekend’s chapter seven of the Book of Revelation, six seals have been opened on God’s scroll and disaster is coming to earth. The sacred author pauses in this chapter to learn who will be able to stand before those approaching events (6:17). An angel carries God’s seal in order to seal 12,000 people from each of the twelve tribes of Israel. This Old Testament imagery is fulfilled in New Testament terms as John the Revelator sees in Heaven more people than can be numbered who have come from all nations. They wear robes that, through tribulation, have been washed in the Blood of the Lamb, rendering those robes white.

This same use of white robes and being sealed are incorporated into the Rite of Baptism. This multitude in Heaven worships the Lamb and God on His Throne. So, the theology of Baptism is deepened by the Book of Revelation. Whether Baptism is framed in terms of its Trinitarian formula or described as the sealing of the saints, being incorporated into Christ does not exempt the baptized from sickness, betrayals, wars or other calamities. However, participation in baptism signals God’s presence in and around the baptized, through and beyond this life.

The eschatological tension between the already, and not yet orients the readers of Revelation to a life in these in-between times. Moreover, it serves to highlight the nature of the Church in the eschatological and heavenly perspective. The ecclesiastical question is addressed in this chapter where John informs readers of two kinds of churches, namely: the church militant, which is the earthly earth and the church triumphant, which is the heavenly Church where those dressed in white robes stand before the presence of Almighty God and the Lamb. God will always protect His people, and this divine security is hidden from humanity because the mystery of death and God’s presence in the chaos of life is too often unfathomable. The lesson revealed in chapter 7 is that in persecution, the reality of God’s protection on the faithful is authentic and real.

The sealed number of God’s people in 7:4 that John is made to see is indeed the triumphant (or heavenly) church, whose voices proclaim God’s action of deliverance. In fact, their loud voices can also be interpreted as a testimony to their salvation. The heavenly multitude claims God’s victory because they were martyrs who had shed their blood as a form of witness to Christ. Their celebration is not just for their salvation but they celebrate their triumphant passage by faithful perseverance through persecution. In other words, witnessing is not just claiming to be a Christian but it means triumphant participation through one’s own death and experiencing the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ. The emphasis is not that all Christians must shed blood as a form of testimony but rather that all who believe are candidates who are subject to tribulation in one form or another, in whatever comes their way. Such tribulation is paramount to follow the Lamb’s way. The futuristic perspective of Revelation’s framework gives hope to Christians enduring present struggles that determine their future with God, the Lamb and the Holy Spirit. Those who face such challenges with faith and trust in God are the ones who are participating and being washed in the blood of the Lamb and have been sealed by their baptism to go through life’s varying seasons.

The two pronged question raised by the elder to John is also the question for the present community of faith, “Who are those robed in white, and where have they come from?” First, the elder informs John about the nature of the crowd as those who have come out of “the time of great distress”; this is the ordeal of tribulation and trial that God’s people must faithfully endure. While John does not note that Jesus is part of the ordeal, interpreters must not miss the point that the Lamb was the harbinger of the great distress, which the New Testament refers to as the life, death, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus or the Paschal Mystery.

Excerpted from http://www.workingpreacher.org. Israel Kamudzandu. “Commentary on Revelation 7:9-17.” 17 April 2016.