Parrhesia: boldness – openly – supreme apostolic virtue

One of the greatest Catholic theologians of the 20th century was a Swiss priest named Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar. He once pointed out that one of the most frequently used words in the Acts of the Apostles was the Greek word parrhesia (Gk. παρρησία), meaning cheerful boldness in the face of danger or opposition. He believed that without such boldness, Christianity would have stalled in Judaea. In other words, the faith would never have spread to Antioch, Greece, and Rome.

In the three Synoptic Gospels, only Saint Mark uses the term parrhesia, which is found in a central point in his Gospel situated between Peter’s profession of faith and immediately after the first foretelling of the passion. He wrote, “[Jesus] spoke this openly” (parrhesia) (Mk 8:32). In the Gospel of John, Jesus often speaks openly or plainly (parrhesia) both with His disciples (Jn 11:14; 16:25, 29), as well as to the world (Jn 18:20). It is true that when Jesus spoke of the mysteries of the Kingdom of God, He sometimes communicated His message in parables, but in His moral teachings the language He used was frank or bold because the Lord wanted the same to be true for all, “Let your ‘Yes’ mean ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No’ mean ‘No.’ Anything more is from the evil one” (Mt 5:37). This bold quality of Jesus was recognized even by His adversaries: “Teacher, we know that you are a truthful man and that you are not concerned with anyone’s opinion; You do not regard a person’s status but teach the way of God in accordance with the truth” (Mk 12:14).

Freedom of speech as exercised by Jesus can also be inferred in His capacity to recognize who is on the path of righteousness (“Blessed are you…”) and who, on the other hand, is on the path to perdition (“Woe to you…”). Jesus also knows how to speak kind words, as in “Courage, child, your sins are forgiven” to the paralytic (Mt 9:2) or “Courage, daughter! Your faith has saved you” to the woman suffering the loss of blood (Mt 9:22). However, He can also speak harsh words like “Why are you testing me, you hypocrites?” (Mt 22:18) or calling the Pharisees “blind guides!” and “whitewashed tombs” (Mt 23:16, 27).

In the Acts of the Apostles, frankness in announcing the Gospel becomes the courage given by the Holy Spirit in situations of persecution, “…they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and continued to speak the word of God with boldness (Gk. μετὰ παρρησίας)” (Acts 4:31). Understood in that way, you could describe parrhesia as the supreme apostolic virtue. However, the Christian innovation associated with that attitude primarily has to do with someone’s relationship to God. Imbued with the Holy Spirit, given at baptism, the Christian can turn to the Father “in total confidence” as a child who “dares to say” “Abba, Father!” Parrhesia is, therefore, this trust in the love of God, love that God manifests when hearing the prayers that are offered up, love that God will manifest on the day of judgment (1 Jn 4:16).

Within the Christian community, filial relationships should be characterized by frankness, yet, always with an eye toward charity. Fraternal correction requires gradualness, but is meant to be practiced (Mt 18:15-17; Gal 6:1). Clearly immoral behavior, like that described in 1 Cor 5:1 (a Christian who lives with the wife of his father) cannot be tolerated: “Do you not know that a little yeast leavens all the dough? Clear out the old yeast…” (1 Cor 5:6-7). Paul wants to speak to the Corinthians (2 Cor 7:4) “with great pride (or boldness)” (Gk. πολλή παρρησία ) and desires that among themselves, believers have a true love, not a fake, hypocritical type (Rom 12:9). Therefore, he says, “We urge you, brothers, admonish the idle, cheer the fainthearted, support the weak, be patient with all” (1 Thes 5:14). And if someone does not obey and rebels, it is to be pointed out in public. “Do not regard him as an enemy but admonish him as a brother” (2 Thes 3:15).

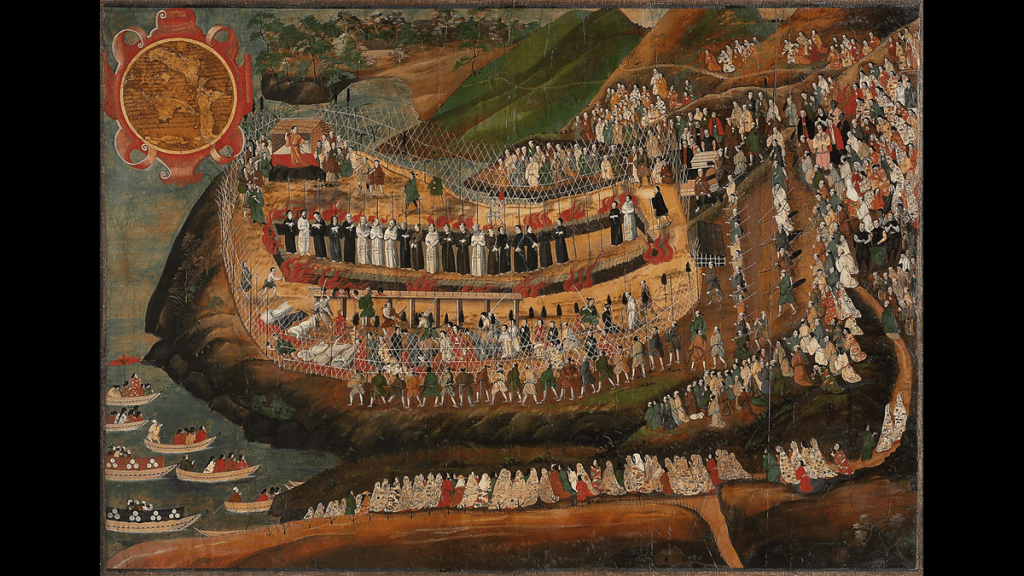

Finally, when the Gospel was being put on trial, Christians exercised parrhesia before the public authorities, taking on the attitude of the prophets of the Old Testament who were not afraid to announce the word of God, even to the point of risking their lives. In fact, anyone animated by the spirit of the Gospel refuses both the theocratic ideal, which forces the reign of God to coincide with the State, and also the totalitarian pretenses of a pagan State. Christians were loyal citizens; they prayed for the Emperor and for the public authorities, but they refused to obey those orders or customs that involved a recognition of idolatry or denigrated human dignity. For this reason, “the martyr is the ‘parrhesist’ par excellence.” Here, one can see how parrhesia can be expressed even without words, in refusing to carry out a determined act for reasons of conscience. In the case of the martyr, the courage of confessing the faith goes hand in hand with rejecting a specific request that implies a denial of the faith, be this an act of idolatry or of blasphemy against Christ.

Excerpted from – Enrico Cattaneo, SJ. “Parrhesia: Freedom of Speech in Early Christianity. La Civilta Catollica October 14, 2017